Deliciously Different — Savoring Shiitake in a Magical Land

As soon as you arrive in Takachiho, there is a strong sense of the otherworldly. This town in Miyazaki Prefecture, almost exactly in the middle of Kyushu Island, is an old place, a town filled with ancient legends, gods and goddesses.

In fact, many of the foundation myths of Shinto, Japan’s endemic religion, occurred here. Nearby Amano Iwato Shrine is dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu. Legend says she quarreled with her brother and hid in a cave just behind the shrine, plunging the world into darkness. Millions of deities gathered at Amano Yasukawara, an actual shrine within a large cave about 15 minutes’ walk from the main shrine, to decide how to coax the goddess out of hiding. The entire story, including her eventual return to the world, can be seen in the kagura, ceremonial dances performed here every night.

Nearby is Takachiho Gorge, perhaps the most famous tourist destination in the area. While the gods also figure in its creation story, geologists say that this deep, cliff-lined section of the Gokase River was formed by four different eruptions of the mighty volcano Mt. Aso.

One more wonderful, magical and yet very real thing found here is shiitake mushrooms. Not just any fungus, says Kazuhide Sugimoto, president of Sugimoto Co., Ltd.: “Takachiho shiitake is unlike any other.” Sugimoto is not only one of the biggest shiitake distributors in Kyushu and a grower himself, but he is a passionate evangelist for his product. He is active on social media; he travels often to major cities worldwide, visiting trade shows and Michelin-starred restaurants, making the pitch for Takachiho shitake. Often it’s in a rather humorous shiitake headwear: “It catches attention, but I don’t want to become a character myself,” he explains. “I want the attention to be on the shiitake mushrooms.”

People are taking notice. Sugimoto says that he often receives comments from people overseas about how the shiitake is rich, flavorful, like meat; in Japan they are known as the “abalone of the mountains” because of a firm texture and richness similar to the shellfish.

The secret begins with log cultivation, a method used for more than 1,000 years, but which Sugimoto has improved upon. “We take lengths of kunugi (sawtooth oak) wood, drill holes in a regular pattern and insert plugs (these contain shiitake mycelium, the stringy main body of the mushrooms),” Sugimoto explains. These are set out in the woods, two rows of narrow logs set leaning against each other at a slight angle with supporting fencing in between. “What we did, though, is to set the cut logs out in bamboo fields, rather than in an oak forest. The canopy of leaves gives just the right balance of light and shade for the best growing condition, and bamboo also has positive effects on the soil and air around the mushrooms.”

Another bit of magic can be seen in the early mornings from the hills above the shiitake fields. Unkai, literally a sea of clouds, flows through the valleys below in the pre-dawn light. That sea of clouds covers the shiitake with dew—just enough water for slow and steady growth. Growers only need to provide logs for the shiitake to grow on and water, but too much water and warm temperatures will make the mushrooms grow too fast, and make them less flavorful. One taste tells you that is not a problem here, and the unkai becomes not just a beautiful, cool morning mist in the valleys but a key reason for the Takachiho shiitake’s superiority.

It takes a few years for the mushrooms to begin to grow on the logs; then, after about six years, the logs themselves begin to break down and become spongy. The logs come from trees on unused land; only the part of the trunk or branches that are about 25 centimeters in diameter are needed, so the rest of the tree is split for firewood. The spent logs are collected and piled up to decompose, and can be used for things like mulch or biofuel. In short, almost nothing is wasted in the process.

In fact, Sugimoto says, shiitake cultivation takes the forest from sustainability to regeneration. “When the oaks are cut down, sunlight bathes the forest floor, allowing new shoots to grow from the stumps along with other new undergrowth, so new trees emerge on their own.” Those new trees will help the mountain slopes to retain water and prevent erosion, and young trees absorb more CO2 than older ones. So, he says, growing shiitake results in the mountain regenerating in about 15 years, without the need to plant trees.

One more thing is unique to the Takachiho shiitake Sugimoto grows: it is a dried product, not fresh. “Fresh only has a shelf life of a few days, while our dried product lasts longer, is portable, and has better umami,” that Japanese-named fifth sense of taste that now is a standard term worldwide. “The secret to our shiitake’s flavor is that we quickly dry them immediately after harvesting, using two passes through our exclusive far-infrared drying system. This dramatically reduces the water content, while ensuring top flavor.”

Special workers carefully hand-finish dried shiitake, which will be used in high-end New Year delicacies

During cleaning, broken bits of shiitake and deformed mushrooms are removed

Sugimoto brings us to a small work area in the farm office. Seven workers, all physically or mentally challenged individuals, are diligently scraping away the tough stem of the mushrooms, then carefully cleaning the caps. “Mushrooms are a natural product, so we have to clean away dirt and bugs and things. Our team here is very focused on this, and does a great job. They get paid exactly the same as anyone else in our factory, because their work is very important.” They are so skilled at this process, in fact, that Sugimoto Co. easily won kosher certification.

Sugimoto displays his company’s other main product: shiitake powder. “We wanted to do something with mushrooms that were too small or poorly shaped to sell,” he says. “So we tried making a powder from them that could then be added to other dishes.” What they discovered was that the shiitake powder, almost tasteless by itself, hugely boosts the sense of umami in other foods. “Dried shiitake contains guanylate, a natural umami booster,” he says. Chemically, it reacts with inosinate, a chemical found in meat, fish and other materials, and glutamate, to greatly amplify the sense of umami—in fact, up to 30 times what would ordinarily be sensed.

“But it’s not like MSG or other chemical additives,” Sugimoto stresses. “I like to say that those sit on top of the flavor, while our shiitake powder acts from below, more naturally, more elegantly and more deliciously.”

Sugimoto’s shiitake is a wonderful choice for vegan and vegetarian eaters, with the high vitamin D content, helped by a special process Sugimoto Co. developed, especially welcome for a group that often seeks sources of vitamin D.

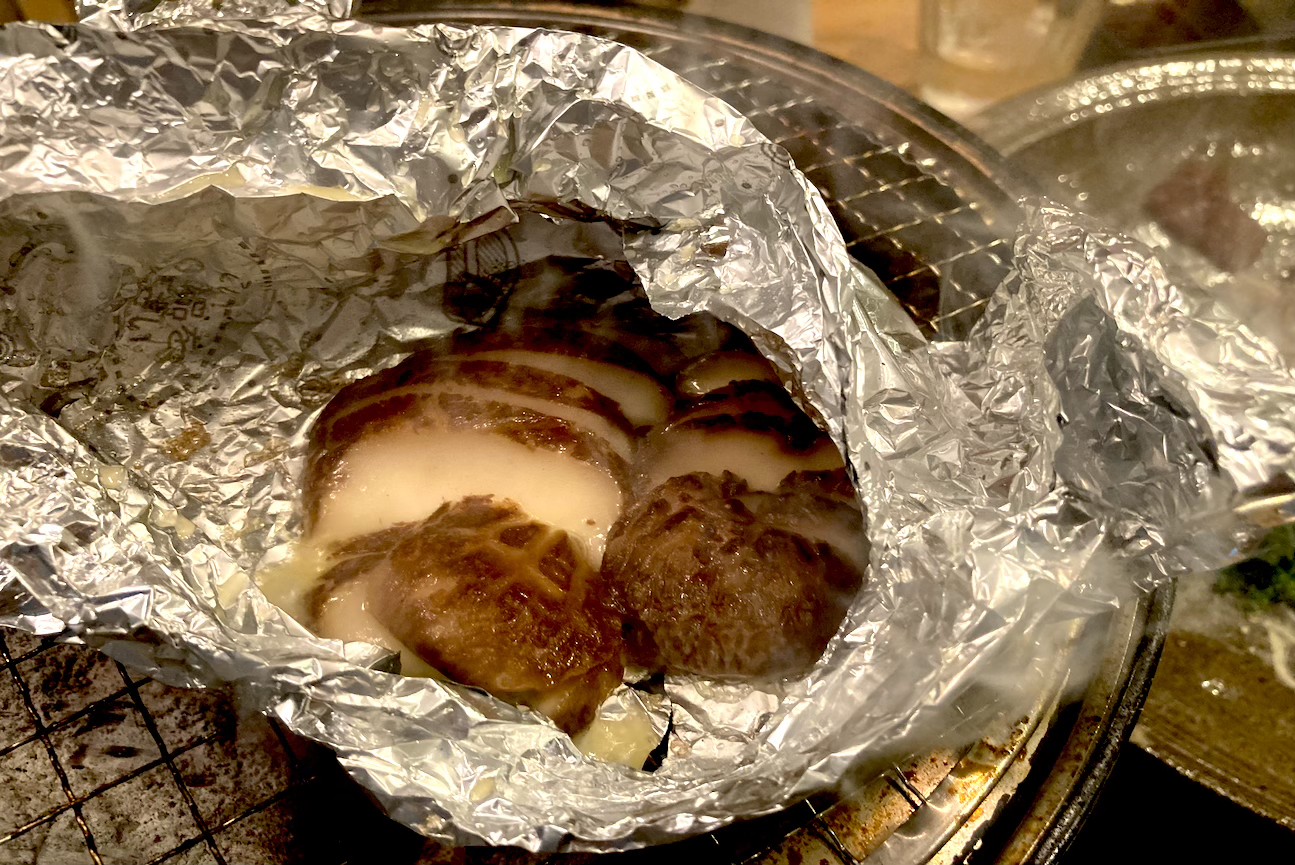

Sugimoto prepares a favorite recipe for his dried mushrooms: the mushrooms are soaked in cold water, in a refrigerator, overnight, then sliced, covered with butter and grilled in foil. When the foil is first opened the difference from the dried source is striking: the look is plump, dark, shiny; the taste is rich and meaty, the texture firm and succulent. And delicious.

Sashimi, Takachiho style, likely doesn’t come from the ocean

Tanada, the rice terraces of the area

Takachiho is also known for its meat products, including Takachiho beef, and Miyazaki Jitokko, a trademarked name for the local chicken. If you order sashimi here, it’s likely not to be fish but raw beef, horse and chicken (you know they’re confident if they serve raw chicken meat!). The Takachiho area is covered in tanada, terraced rice fields rising up toward the forested mountains. On some cleared slopes black cows graze their way across their steep pastures—the source of the beef, some of the best wagyu in Japan.

A wide variety of some rather elegant shochu

Shochu aging in barrels in the constant temperature and humidity of a tunnel to nowhere….

One accompaniment for those very enlightening meals is Kyushu’s favorite beverage: shochu. It can be made from rice, potatoes, barley, soba (buckwheat), even chestnuts, and the quality here means it’s worth sipping. An interesting detour on the way out of town is the Tunnel Station, a tunnel for a railway going nowhere. A new line was planned for the area, with this tunnel successfully completed—but construction of the next tunnel down the line caused a rush of groundwater and forced the cancellation of the rail line. The now unused Tunnel Station, with its constant temperature and humidity, became the ideal place for local distiller Kagura Shuzo to age its special barrel-aged shochu.

And that shochu is the perfect, special drink to toast a great trip to a delicious, inspiring, otherworldly part of Kyushu, Takachiho. Of course, clean Miyazaki shochu goes great with rich Takachiho shiitake—and both make great items to take home and remember travels in a magical land.

Enjoying Takachiho shiitake and other local delicacies with saké served from a bamboo warmer

TAKACHIHO SHIITAKE

RECOMMENDED MIYAZAKI SHOCHU AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE OVERSEAS

KUROUMA taru 40%

This is a premium shochu stored that has been for a long time based on the shochu stored in a barrel for six years. Kagurashuzo ages the barley shochu—which is an optimal shochu for barrel storage— in the clear air of Takachiho in Miyazaki, while letting it breathe little by little, resulting in a sweet mild flavor and a rich mellow taste. Furthermore, by filtering the unprocessed shochu at minus 20 degrees Celsius, a clear aroma is extracted. It is a specialty shochu with a luxurious smooth aftertaste, containing 40% alcohol. KUROUMA taru 40% won the Double Gold Award at the San Francisco World Spirits Competition 2021. This is a testament to the excellence of their shochu, with all the judges awarding a gold prize.

Taste of Summer!

Kuro Kirishima

Kuro Kirishima shochu is distilled from the Japanese sweet potato “Kogane-Sengan” and clear subterranean water known as “Kirishima Rekkasui.” It's notable for its lush sweetness and crisp taste, which comes from the use of black rice koji. It pairs well with strongly flavored dishes such as yakitori and pork belly.

The representative brand of the Kodama distillery. The current master brewer, Kanemaru Junpei, uses Miyazaki Beni sweet potato and the themes of “delicate,” “harmony,” and “lingering” to brew by hand. Miyazaki Beni is characterized by a light, sweet fragrance. Toji Junpei is recommended paired with food, and can be drunk in a variety of styles, from being served on the rocks to mixed with water, hot water, or soda. Ingredients : sweet potato (Miyazaki-Beni, Otsuka Sand), kouji-rice(Miyazaki products)

After high-temperature fermentation using Kagoshima yeast No. 2, we add heat to the MOROMI (main fermenting mash) using our original distillation method. This barley shochu is defined by the roasty flavor you’d expect from warm toast and the sweet char of cotton candy.