The condiment “miso” is the result of fermentation and is a traditional food of Japan brimming with savoriness

“Miso” (fermented soybean paste), an essential part of the Japanese diet, is a traditional ingredients in Japan. Simple ingredients are transformed through fermentation in this condiment, which has continued to be carefully consumed, as a kind of cure-all, throughout its long history of over 1,000 years, and still adorns our dining tables today. “Miso” is closely connected to the traditional food culture rooted in each area of Japan, resulting in a rich variety of flavors formed over long years, and now, alongside the worldwide boom for Japanese cuisine, it is attracting increasing attention overseas too.

“Miso”’s ingredients are just soybeans, salt and a koji. It has a deep and profound, yet simple, flavor.

Miso, essential to the story of Japanese cuisine and drawing notice as a fermented food unique to Japan, is a mixture of soybeans, koji (mold) and salt, which is left to ferment and age. The basic manufacturing process is very simple: (1) Steam soybeans (2) Allow koji starter (Aspergillus oryzae) to adhere and make koji (3) Mix soybeans with koji (4) Leave to ferment. Because it is made from just three ingredients, there are infinite possibilities for distinctive characteristics to emerge according to the maker. According to the amount of salt, percentage of koji, length of fermentation and aging process, as well as the climate of the producing land, too, it can display exquisite differences in taste, color and texture. In common with wines of the world, it is as if its flavor comes from the land and climate. “Miso” can also be largely classified by what the “koji starter”, the type of koji that determines the flavor, is adhered to. Cultivating “koji starter” on rice produces malted rice, barley, malted barley, and soybeans, malted soybeans. According to the koji that is mixed with the raw ingredient of steamed soybeans, miso can be divided into “rice miso”, “barley miso”, “soybeans miso” and a combination of these: “blended miso”.

From top: “soybean miso”, “rice miso, “barley miso”. Not only do they look different, but their textures and flavors differ too, and combining them gives birth to yet new tastes.

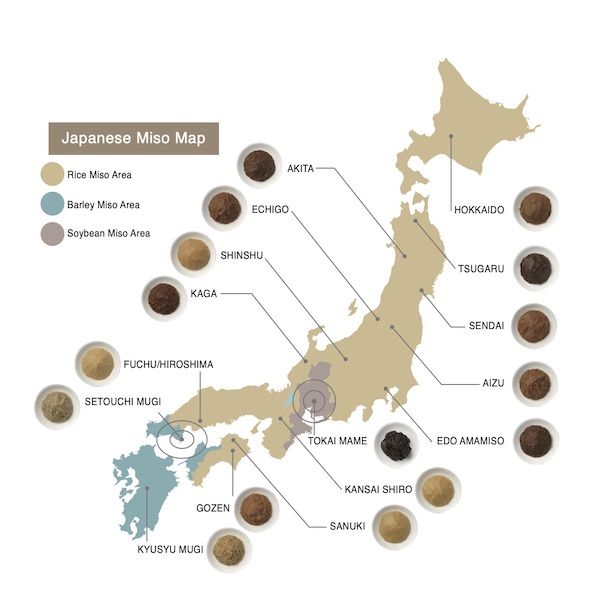

In other words, “miso”, like sake and soy sauce, is a fermented food created by the power of microorganisms such as yeast and bacteria. Japan, with its frequent rainfall and high humidity, can propagate koji starter easily, so it is really suited to making “miso”. Also, the Japanese archipelago has a landform that is long and thin running north to south, so that in the same season the climate and temperature are quite different in the north and the south. This means that fermentation and aging process differ slightly too and the koji in use changes by region, thus local “miso” exists that is quite unusual in look and flavor. Another feature is the link with food culture such as local dishes using “miso” that are rooted in each region: Hoto of Yamanashi, Ishikari-nabe of Hokkaido, Hoba-miso of Gifu, Satsuma-jiru of Kagoshima, etc.

There are as many as 16 types that are established as local “miso”. Quoted from Japan Federation of Miso Manufacturers Cooperatives “Welcome to Miso Soup Wonderland”.

“Miso” of varied kinds of flavor and taste, like spicy or sweet, is used with different seasonal ingredients according to the season, and different types of “miso” can be combined. Bringing out flavors in this way is a culinary skill unique to Japanese cuisine. “Soup and three side dishes” is the basic style of Japanese cuisine in households in Japan, with “miso soup” using seasonal ingredients center stage. From tofu, wakame seaweed, leeks, daikon radish, fried tofu, etc., to one’s own ideas for using seasonal vegetables to accompany the mixture of “soup stock” and “miso”, there are no rules for what you can put in miso soup. Miso soup supplements the proteins and vitamins that tend to be lacking in white rice, so in the Japanese diet that has rice as staple its consumption is wisdom itself: simple, rational and full of flavor. Of course, there is not just miso soup: “miso” goes well with any ingredients, and it excels at bringing out the flavor of raw ingredients. There are various methods for using it, such as mixing it with oil in a “miso fry”, taking away the raw smell from meat and vegetables in a “miso simmer”, or making food last longer in a “miso marinade”, and there are also differences in usage and cooking method according to region.

“Miso soup” is make by just mixing together soup stock made from dried anchovies, dried bonito, etc., soup toppings and “miso”. It is nutritious, with a comforting taste.

There was a saying in the Edo Period, “Rather than pay money to the doctor, pay it to the miso-seller”, and “miso” was said to contain the essence of flavor, life and beauty, being carefully eaten in the way of a cure-all. In addition to the high-quality protein from the main ingredient soybeans, it is rich in amino acids and vitamins generated through fermentation. It is like a treasure chest of goodness, a concentration of a multitude of nutritious elements such as carbohydrates, lipids, minerals and dietary fiber.

Along with the expansion of Japanese cuisine on the world scene, Japan-born “miso” too is now widely available overseas. A style has emerged called “miso condiment” that involves making original, home-made seasoning by combining it with other condiments like olive oil, red wine, curry powder and coffee beans, and “additional miso” adorning a normal meal is also something to enjoy. In recent years, the possibilities for “miso” have also been noticed by overseas chefs, who have given birth to a new “miso” taste that transcends nations, from desserts such as macaroons to the secret ingredient in white sauce, etc. “Miso soup” is also popular overseas, with little “miso balls” also appearing on the scene for instantly making delicious “miso soup”. “Miso balls”, a mixture of anchovy powder, dried bonito shavings and miso rounded by hand and topped with powdered green tea, green laver, etc., are also gathering interest overseas for their fun appearance. Healthy and with a deep, profound taste, “miso” is a food full of possibilities, the extent of which is yet to be seen.

“Miso balls” are miso mixed with dried bonito or dried anchovy powder to make the soup stock, rounded into balls. Just pour on hot water to create delicious miso soup.

[Fermentation]

Essential to the manufacturing process of “miso”, as well as other Japanese consumables such as sake and soy sauce, is “fermentation”. “Fermentation” is the working of microorganisms beneficial to humans to break down matter. “Koji” is necessary for fermentation, and include: lactic acid bacilli needed for making cheese and yogurt, koji starter generated by amino acids that create savoriness, yeast that breaks down sugars, natto (fermented bean curd) bacteria that improves the intestinal environment, and acetic bacteria that changes alcohol into acetic acid. “Fermentation” does not just increase the savoriness, nutritious value and shelf life of plants, but also brings about health benefits such as the improvement of the intestinal environment and an antioxidative effect, which have drawn attention in Japan and overseas. In fact, koji starter, essential in “miso” manufacture, has been designated Japan’s “national mold starter”.

References: Miso Culture Journal / Japan Federation of Miso Manufacturers, Central Miso Research Institute

New Edition Knowing Miso / Japan Miso Promotion Board (Miso Online)

Photographs supplied by: amanaimages inc., Japan Miso Promotion Board

Text: Miki Suka