Cooking in the Kingdom of Fermentation: The Traditional Flavors of the Noto Peninsula

(Konka iwashi sardines are fermented in nuka rice bran. While similar to anchovies, the flavor is more intense, and gets stronger the longer it is left to mature. photo: AKIRA YUASA)

Benjamin Flatt’s Japanese mother-in-law stared at him as he chewed. She had just handed him a bowl of rice topped with a small portion of konka iwashi, fermented sardine, and he had scooped it into his mouth without hesitation. “She was watching me intently, waiting for me to say ‘I hate this,’” Flatt recalls. “But I was experiencing this incredible, delicious flavor. It was amazing, and I absolutely loved it.”

That was the Australian chef’s first encounter with the fermented food culture of Noto, a remote peninsula jutting northward like a crooked thumb into the Sea of Japan. It was 1996, and he had recently arrived with his wife, Chikako Funashita, to help at her parent’s inn. He had grown up living and working in a restaurant run by his family in rural Australia, with a farm-to-table approach to using locally harvested ingredients that is natural when you’re living in the middle of nowhere. So while he wasn’t totally caught by surprise by the rugged Noto landscape and the thriving, unique food culture, it was still a bit like being dropped into another world.

Benjami Flatt and his wife Chikako Funashita run Flatt’s Noto, a restaurant and guest house on the Noto Peninsula. photo: AKIRA YUASA

He wasn’t exactly intimidated either. He was no stranger to strong cheeses, blue cheeses, “all that type of stuff.” But this was on another level. The konka iwashi sardine of his first encounter had been left to ferment in rice bran for over a year. Yet the silvery fish looked as fresh as the day it was landed. “I was wondering, ‘How does something left in a bucket that long not kill you?’” he says. But Flatt was hooked, and became an avid student of the food culture of his adopted home. He and Funashita began to make their own konka iwashi, along with many other fermented ingredients, for use in the Italian dishes served at Flatt’s Noto, a restaurant and guesthouse they opened in 1997.

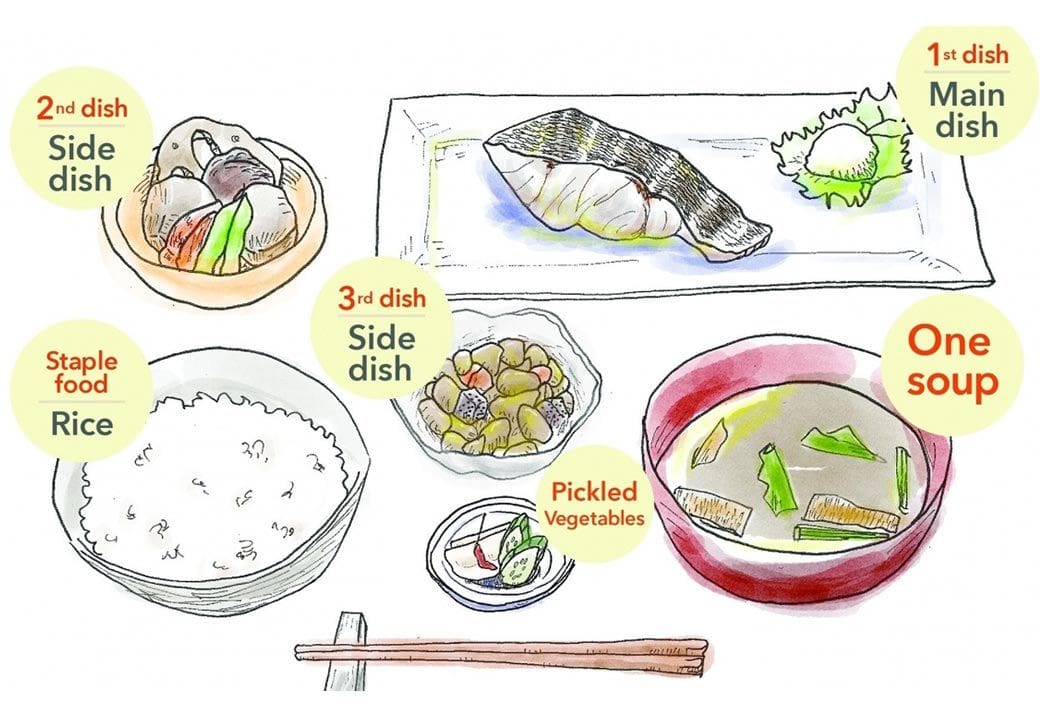

Noto is called the Kingdom of Fermentation, a bold statement considering Japan’s widespread cultural and historical connections to pickling and fermentation. But the claim is not to be scoffed at. The region’s isolation demanded self-reliance, and the climate—hot, humid summers followed by bitterly cold winters—created the ideal environment for optimal fermentation. The fertile seas and mountains also meant there were plenty of ingredients to work with. Traditionally, fermenting was for self-sustenance, with each household making their own fermented goods, and that is generally how things remain. “When visiting someone at festival time, for example, we’re often offered some fermented family dish made by the grandmother,” says Flatt.

The Shiroyone Senmaida rice fields are designated as a “national cultural property scenic spot” and represent the importance placed on traditional methods of production.

Recent years have seen Noto’s fermented food culture garnering wider interest and appreciation. In 2011, the UN’s FAO recognized the region’s agricultural system, which integrates aquatic and land-based ecosystems, as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System. In 2024, Noto’s unique fish-based sauce, ishiri, received Geographical Indications (GI) status, recognized as one of the country’s three primary fish sauces, and was also registered as an Intangible Folk Cultural Property.

Ishiri is fermented in winter, which slows the process while ensuring that it doesn’t spoil before fermentation begins. “To give you an idea of how micro the culture is, we make it with salt and squid organs, while only 50 kilometers away, they make it with mackerel and sardines,” says Flatt. “It has twice the umami value of soy sauce,” he says. “If I add ishiiri to the potato soup, you’ll taste and smell it in the background, but the real flavor will be the potato, which gets a big umami boost from the sauce.” He also uses the sauce in other dishes like squid-ink pasta—the ishiri forming a black sauce beneath a white cream sauce topped with squid—the flavor increasing with each bite.

In other dishes, ishiri becomes a replacement for salt. Instead of adding salt in a carbonara pasta, for example, Flatt uses ishiri to bring out the flavor. “In fact, it’s gotten to the point where, if I didn’t use it in my cooking, I’d think something is missing,” he says.

One Italian dish incorporating ishiri is this squid ink pasta—white cream sauce for the noodles on top of ishiri flavored squid ink topped with squid rings. photo: AKIRA YUASA

The konka iwashi sardines that marked his first experience with Noto fermentation are fermented in nuka rice bran, salt and chilis. The flavor is similar to anchovy, but more intense with umami, as the oil used in anchovies dilutes the flavor. “The rice bran holds the flavors in the sardines, and also absorbs a little bit of the flavor itself,” says Flatt. “You can start using it after three to six months, but like any fermentation, the longer it’s left the more mature, more intense it becomes.” While konka iwashi is traditionally grilled and served on rice, he has found it to be superbly adaptable, using it in pasta dishes like aglio e olio or pepperoncini, Caesar salads, and as a base for dashi.

A particularly unique food is Noto’s hinezushi, a style of sushi that long predates the Edo-mae version that comes to mind when most people think of sushi. The latter is a fast food, while hinezushi developed as a way of preserving the fish and rice for long periods of time. It consists of layers of bull mackerel and rice, the leaf from a fragrant Japanese pepper tree called sansho and chillis. It undergoes a lacto-fermentation, meaning it continues fermenting and must be eaten within three months. “We call it ‘cheese of the sea,’” says Flatt. “It’s not very well known, and is a bit of an acquired taste, but it’s delicious.” He uses it in dressings, as an appetizer, or in sauces.

To make hinezushi, bull mackerel is layered with rice and fragrant sansho peppers. “We call it ‘cheese of the sea,’” says Flatt. photo: AKIRA YUASA

The couple makes all of the above Noto specialties at home, and that’s just the beginning. They also prepare their own miso, dry preserve kingfish prosciutto-style, and pickle daikon radishes, umeboshi (sour plums), and mountain vegetables. “It’s a year-long cycle of production that not only keeps us busy but keenly aware of the seasons,” says Funashita.

Fermentation is a year-round business, with various ingredients prepared according to the season. photo: AKIRA YUASA

When the devastating earthquake hit the Noto peninsula on New Year’s day in 2024, they closed Flatt’s down to help with the area’s recovery and reconstruction. They have since focused on preserving Noto’s food culture, especially as ingredients became harder to source from damaged fields, forests, and fisheries. They established an NPO called Noto Support, interviewing local women about their cooking traditions. They recovered 3,000 sets of prized Wajima lacquerware, storing them for when people return. In addition, they have held events in Tokyo and elsewhere, introducing Noto cuisine in hopes of keeping the culture alive. The restaurant reopens in April, 2025.

They hope that visitors drawn to the region will be similarly appreciative of what Noto has to offer, and willing to immerse themselves in Noto lifestyles. Flatt emphasizes the long history of Noto food culture, attributing its longevity to the region’s ample supply of everything needed to live on. “Noto will keep going,” he says. “People will continue to appreciate the beauty of the land and the flavors of the food. Hopefully, with our help and the help of many young people of Noto, we can keep this important food culture alive.”