Take a moment to relax Japanese-style with tea and wagashi (traditional Japanese confectionery)

Wagashi are traditional Japanese confectioneries that often reflect the changing of the seasons. They are rooted in the culture and customs of Japan, and have long been a part of everyday life in the country. Having tea with family and friends over tea and seasonal wagashi can be a rare moment of respite in our busy modern lives. Here, we discuss the history of these traditional confectioneries and describe the most well-known wagashi, and how to enjoy them.

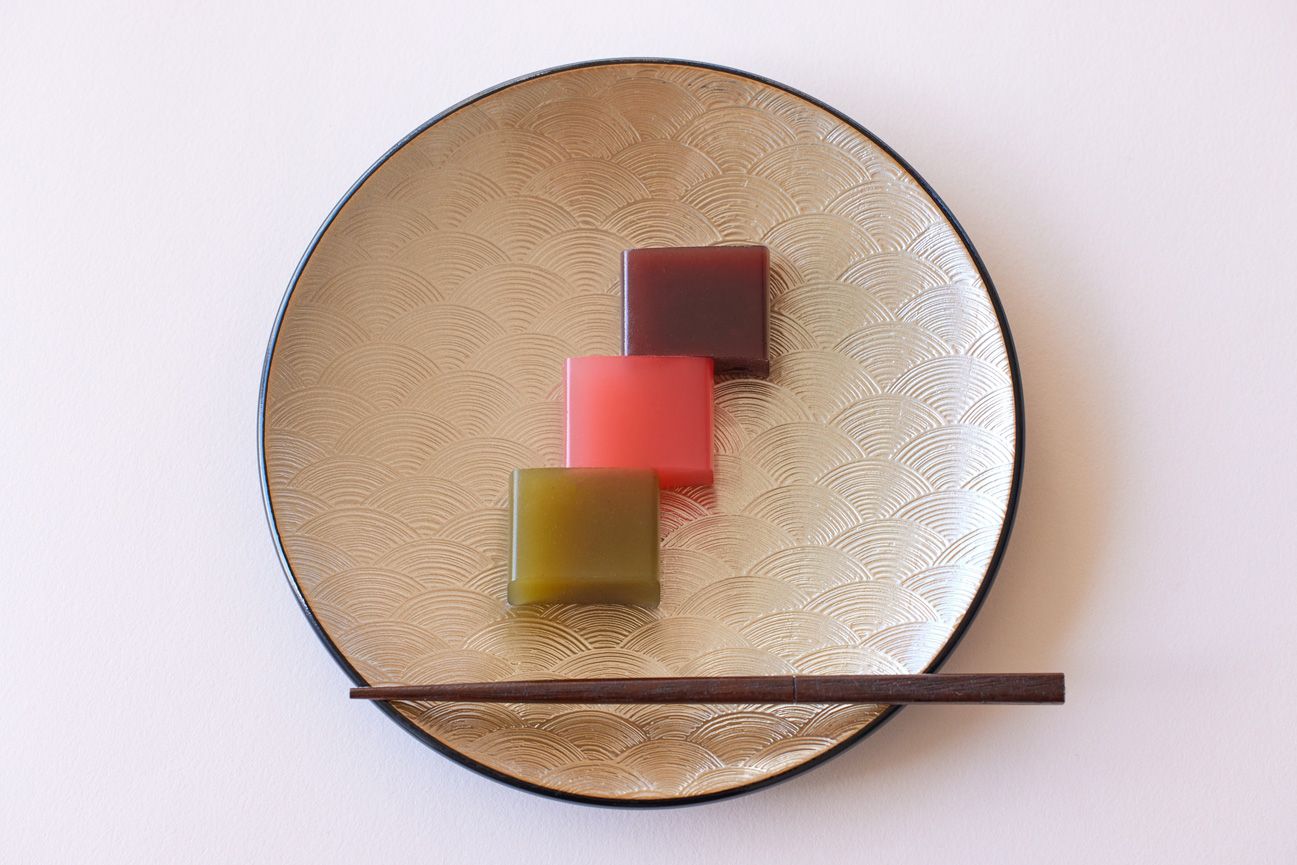

Jonamagashi (intricately designed fresh confectioneries) made in spring-like motifs. Clockwise from top: “Haru no Yume (Spring Dream),” a joyomanju (steamed yam-based bun), based on the Chinese parable, “The Butterfly Dream”; “Sadoji (Sado Island Road),” which evokes the scenery of Sado Island, with canola flowers blooming; and “Taorizakura (Hand-Picked Cherry Blossom),” which expresses the beauty of cherry blossoms. (Confectionery by: Toraya)

Inside “Taorizakura” is shiro-an (white bean paste). The light, gentle sweetness of the confectionery brings out the flavor of the matcha green tea.

First, let’s look back on the history of wagashi. Back in ancient times, kashi (the gashi of wagashi, meaning “confectionery”) actually referred to nuts and fruits - as can be seen in the fact that we still call fruits mizugashi (“water” confectionery) today. Because sweet foods were so scarce, these nuts and fruits were treasured for their sweetness. Kashi in Japan are also said to be derived from the mochi and dango (rice dumplings) that were created back then, from crops like rice and millet, with these traditional foods evolving rapidly through the influence of foreign foods. Togashi*1, which was introduced from China in the Asuka to Heian period (late 6th century to the late 12th century); tenjin*2, which was introduced to Japan in the Kamakura to Muromachi period (late 12th century to mid-16th century) through Zen monks who had studied in China, and Chinese visitors to Japan; and nanbangashi*3, which was introduced the late Muromachi to early Edo period (mid-16th century to early 17th century) through Japan’s interactions with Portugal and Spain. The influence of these three foreign foods, and the evolution of the tea ceremony, resulted in the emergence of distinct Japanese kashi (wagashi), with their own colors, shapes, and names, in the Edo Period. Kashi with designs and names associated with seasonal customs grew more popular around the Genroku period (late 17th century to early 18th century), primarily in the Kyoto area. These kashi, called jogashi, are said to be what today’s jonoamagashi are derived from.

*1 Togashi: Confectionery introduced by Japanese envoys to the Tang dynasty in China. Many of these were made of rice or wheat flour, came in various shapes, and were deep-fried in oil. They were used in rituals and other events.

*2 Tenjin: Light snacks consumed between the morning and evening meals. Today’s manju (steamed buns) and yokan (gelled sweet bean paste) are derived from some of these confectioneries. The literal meaning of yokan is “mutton broth.” As such, it’s theorized that yokan at the time was a vegetarian dish that used ingredients like azuki beans to create the appearance of mutton.

*3 Nanbangashi: Refers to boro (traditional egg biscuits), castella (honey sponge cake), konpeito (traditional colored sugar candies), and other confectioneries introduced to Japan through trade with Portugal and Spain. They are often made with chicken eggs and large amounts of sugar.

The star of many wagashi is an, a sweet bean paste made from azuki beans. The quality of the an - made by simmering azuki beans with sugar - often determines the quality of the wagashi itself. The wrapping or cover of the an, for instance in confectioneries like manju and monaka (red bean paste sandwiched between wafers), is made with wheat and rice. With rice, there’s uruchimai (white rice), which is typically eaten as is, and mochigome (glutinous rice), which is typically turned into mochi. These can be processed into joshinko (white rice flour), shiratamako (flour derived from glutinous rice which has been soaked before being dried and grounded), and mochiko (flour grounded from dried glutinous rice), depending on the type of rice used. Agar, one of the ingredients used to make yokan, is made from seaweed such as agar weed. Other commonly-used ingredients in wagashi include nuts and fruits, such as chestnuts, Japanese persimmons, and walnuts, that have been eaten since ancient times. Indeed, wagashi evolved over many, many generations alongside various natural ingredients.

Monaka consists of an sandwiched between wafers made with mochiko. Enjoy the contrast between the light, crisp wafers and the smooth texture of the an. Pair with some beautifully brewed sencha green tea. Wagashi is typically served on plates or kaishi (traditional tea ceremony paper). Try your hand at plating by arranging the wagashi on any wooden plates you might own, and more. (Confectionery by: Toraya)

Wagashi are made with plant ingredients, and as such, have garnered attention as a low-fat, healthy snack in recent years. Take azuki beans, for instance. The primary ingredient in an, azuki beans are rich in protein, dietary fiber, and polyphenols, and have been considered an important source of nutrition since ancient times. The red color of azuki beans has also long been believed to ward off evil spirits. This belief is what led to the Japanese custom of eating kashi made with azuki beans, such as botamochi and ohagi (types of rice cake dumplings wrapped in bean paste), in their everyday lives. In Kyoto, they make minazuki (traditional steamed rice cake with azuki beans on top), a wagashi made from azuki beans, for the Nagoshi no Harae (summer purification rites) held on June 30.

There are many wagashi that reflect the seasons - for instance, sakuramochi, which consists of mochi wrapped in salt-pickled cherry leaves, for spring; hina arare (colorful sweet rice crackers) for Hinamatsuri (Girls’ Day); mizuyokan, a smooth, chilled type of yokan, for summer; dango and other confectioneries to eat while gazing at the moon, and kurikinton (candied chestnuts and sweet potatoes) made with freshly-picked chestnuts for fall; hanabiramochi (thin rolled rice cake filled with miso-flavored white bean paste and sweet-simmered burdock root ) to ring in the new year; and more. These wagashi can be found lining store shelves in Japan during their respective “seasons.”

There are also wagashi that have what are called kamei (kashi names), or names specific to that particular configuration of kashi. This is different from the type of kashi - for instance, yokan or monaka. Toraya, a wagashi confectionary company that has been around for about 500 years, is said to have about 3,000 varieties of confectioneries. Some of these have kamei that evoke the sceneries and seasons of Japan, or that have been named after waka (Japanese five-line poems) by aristocrats in the Heian period, historical events in China, and more. Wagashi are sometimes described as “gokan no geijutsu (art for all five senses),” and it’s not hard to see why. You first marvel at their appearance (seeing), enjoy their flavor (taste), subtle aroma (smell), and texture (touch), then hear the kamei (hearing) and imagine the “story” behind the name of the kashi.

There is a truly wide range of wagashi, from the kinds of kashi used in tea ceremonies to more commonplace confectioneries like dorayaki (red bean castella pancakes) and mitarashi dango (rice dumplings with sweet soy glaze). Confectioneries like yokan and higashi (dry pressed confectioneries) that keep well can be bought and stored at home, to be brought out for unexpected guests. As for what to drink - generally speaking, jonamagashi is said to go well with matcha green tea and gyokuro (high-grade sencha green tea), while dango and okaki (savory rice crackers) go well with hojicha (roasted green tea). They can also, however, be paired with drinks other than Japanese teas. For instance, you can pair yokan with espresso, whiskey, or sparkling wine, and castella with black tea or herb teas. Buy several different types of wagashi and try pairing different drinks with them to see what you enjoy.

Confectioneries like castella, dango, daifuku (mochi with fillings), and imoyokan (sweet potato yokan) can be made at home if you have the right ingredients. Serving your guests handmade wagashi - albeit made with simple ingredients - is sure to add some flair to your afternoon tea.

Castella, a nanbangashi, is made by adding sugar to egg, whipping it, combining it with bread flour and honey to make a batter, then baking it in the oven. Adding ingredients like matcha green tea and brown sugar into the batter can give it a more Japanese-style flavor.

Dango are made by dissolving joshinko and mochiko in water, dividing the dough into bite-sized balls, boiling them, putting them on a skewer, and grilling them over an open flame. Mitarashi dango are dango with a glaze consisting of simmered soy sauce, sugar, kudzu powder, and kombu dashi stock. When making mitarashi dango at home, you can substitute potato starch and water for the kudzu powder and kombu dashi stock. Mitarashi dango taste the absolute best when freshly-grilled.

Daifuku, a mochi made with mochiko and filled with an. Daifuku are fun because they can be filled with seasonal fruits - for instance, the ichigodaifuku, which contains a whole strawberry.

Imoyokan are made by adding sugar and agar powder dissolved in water to boiled sweet potatoes, kneading in a pot over low heat until smooth, then pouring the mixture into a mold to chill and harden. They have a gentle flavor, characterized by the texture and flavor of the sweet potatoes.

As wagashi evolved alongside the tradition of the tea ceremony, many wagashi subscribe to the wabisabi worldview - an element of traditional Japanese aesthetics that eschews excess decoration. As such, when setting the table for wagashi, try to choose cutlery that complements the neat appearance of the wagashi themselves. For instance, you could use a green-brown plate that would bring out the colors of the spring leaves, or serve simpler kashi on bon or plates made of natural materials, the key being to consider the overall harmony of the presentation. Enjoy some Japanese-style tea time and savor the passing of the seasons through the gentle, healthy pleasure that is wagashi.

◎ See here for other articles on Japanese teas and snack recipes.

The charm of Japanese tea: enjoying the culture passed down and its wide range of uses

Welcome to the world of matcha, known for its rich aroma and strong flavor

The profound appeal of Matcha tea and Japanese tea, luring Berliners

“Matcha-Flavored Flockensahne Torte” recipe

“Sweet Red Bean Soup with Rice Cake” recipe

Yuko Hama (Dish selection supervision)

Food Space Designer. Involved in floral decorations, interior design, and table coordination. Offers consultations on tableware for traditional Japanese inns and restaurants, as well as planning and staging for parties and other events. In recent years, she has been researching saijiki, almanacs of seasonal words used in haiku, as well as Japanese life and culture, working to offer a lifestyle that is based on the fusion of Japanese and Western styles and highly spiritual design. TALK TCS Vice President and certified instructor. Author of numerous books.

https://hanakukan.jp

Instagram: @yukohama.hanakukan

Hanae Kaede(cuisine)

Gained experience working in the kitchen at Michelin-starred restaurants in France before returning to Japan to study Japanese cuisine in earnest through a specialized course at the Tsuji Culinary Institute of Advanced Studies. Later, after working as a teacher at a cooking school and in product development, she opened her own cooking studio, atelier kafuné, in Tokyo’s Monzen-Nakacho district. Also holds workshops teaching Japanese cooking to visitors and residents from abroad. Published a book of Japanese recipes in France. An English version was also later published.

https://www.kafune-tokyo.com

Instagram: @atelier_kafune

Support by: TORAYA Confectionery Co. Ltd.

Reference: Japan Wagashi Association

Text: Junko Kubodera; Photography: Aya Kawachi