One Cut Above: Japanese Knives’ Connection to Cuisine

Japanese knives have captured the attention of enthusiastic home cook and professionals alike, and many visitors to the country hope to return home with a blade as a useful souvenir of their visit

There is no better place to start the search than in Tokyo’s famous Kappabashi kitchenware district, just a short walk from the sights of Asakusa. Among the many shops aimed at restaurateurs is Kama-asa, a cooking ware and knife store started in 1908 and run by the same family for four generations. Kama-asa specializes in highly functional, simple knife designs made by Japanese artisans and has even opened a branch in Paris.

The Kama-asa knife shop in Kappabashi is always busy with customers looking for the perfect Japanese knife

We spoke with Jérémy Escudero, one of the specialists and sharpeners at Kama-asa, about what makes Japanese knives special, how the blades impact cuisine (and vice versa), along with tips for selecting the best knives for your needs.

Jérémy Escudero of Kama-asa is passionate about the craftmanship of Japanese knives

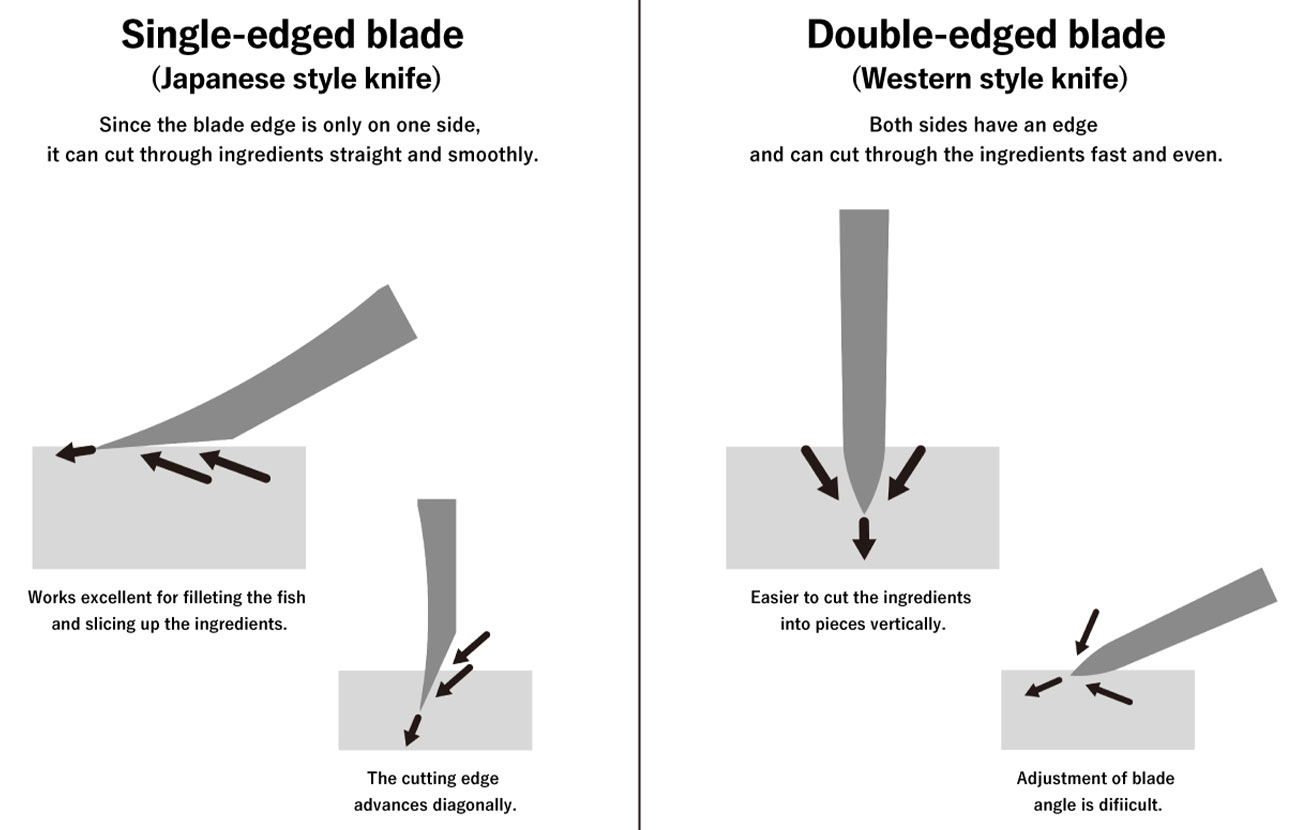

In the simplest terms, the distinguishing characteristic of Japanese-style knives is that they are single-edged. While this may make them thinner and little more delicate than their thicker, double-edged Western counterparts, there is a reason behind this choice. “When cutting through vegetables or fish, the single-edged blades close the cuts as they slice, which seals in the umami and flavor of the ingredients,” Escudero explains. This means that the food will taste better and have better texture, because the cells have not been split, as they would be with a double-edged knife.

Another characteristic of these single-edged blades is that their shape leads you to cut at a slight slant, which is important when slicing fish. This is logical, as most traditional Japanese cuisine is based on seafood and vegetables, as meat was not commonly found on the dinner tables of yore.

Japanese blades are single edged, which make them sharper and allows for clean cuts (Photo: KAMA-ASA)

But knives adapt to the times and changing food culture, and a particularly interesting example of this evolution is the now ubiquitous santoku knife, perhaps the type most commonly found in Japanese households.

During the Meiji Period (1868–1912), meat started to become a more prevalent part of the Japanese diet. Chefs tried using Western style double-sided knives but generally found them a little unwieldy. This resulted in the development of the multipurpose santoku, which is a combination of the traditional rectangular nakiri vegetable knife and a Western-style chef’s knife (or gyuto in Japanese). The broad blade is usually around 160-180mm long, tapering down to a fine tip, which allows for quite close control.

In professional kitchens in Japan, there are a number of more specialized knives you are likely to spot. The deba shows perhaps the greatest difference between Japanese and Western fish cooking techniques. Western fish fileting knives are thin and very flexible, as they are only used to slice the meat off the bone and remove skin. The Japanese deba’s tip is more triangular and thicker, can be used to cut through bone and is essential for the sanmai oroshi fileting technique that is so important in such a heavily fish-based cuisine. This stronger knife allows chefs to divide the fish into two filets and the bony spine while reducing wastage.

Deba knives are made for fileting fish (Photo: KAMA-ASA)

In sushi restaurants you are sure to spot the long thin yanagi knives, which chefs skillfully wield to slice fish in a single stroke without damaging the meat, the secret to those cuts of melt-in-your-mouth sushi and sashimi.

A chef cutting sashimi with a yanagi knife (Photo: KAMA-ASA)

But while the range of blades in the Kama-asa showroom may tempt you to buy a knife for everything from cutting fruit to slicing soba noodles, Escudero points out that a home chef only really needs two.

“A utility knife, which usually have blades between 12 to 15 cm, is what you would use for peeling or chopping smaller ingredients like herbs or garlic,” he notes. “For basically everything else, all you need is either a chef’s knife or a santoku.”

How to choose? “If you tend to chop straight up and down, then the santoku should work best for you. If instead you cut with a rocking motion, then the more rounded off chef’s knife is likely a better fit.”

Escudero repeatedly reminds us that, when selecting a knife, function and feel are of the utmost importance, rather than aesthetics. “It has to feel good and natural in your hand. It is just like shoes: if you don’t feel comfortable or can’t walk well when you wear them, then you will not use them and keep going back to your old beat up pair instead,” he says with a laugh. “A knife that is easier to use and well-sharpened is safer too.”

He also points out that it is important to choose the right type of metal to suit your lifestyle and upkeep ability. “Many people think they should get forged carbon blades, but they require quite a bit of maintenance. A good stainless steel knife is easier to care for, and there is no need to get very expensive knives for regular home use.”

While recommending simplicity, he does give a nod to his French roots and shows off his pride and joy: a handcrafted bread knife. Bringing together the best of Japanese craftsmanship and European tradition, it is another step in the evolution of Japanese knives.

- How to make a Japanese knives (Single-edged knives)

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t-18E6ZOsPs