From a small family-run tea farm to the world!

Ishikawa Seicha has two cultivation bases, one in Hoei Toyota City, a city with a thriving automobile industry, and the other in Shimoyama, an hour's drive away at an altitude of 2130 feet.

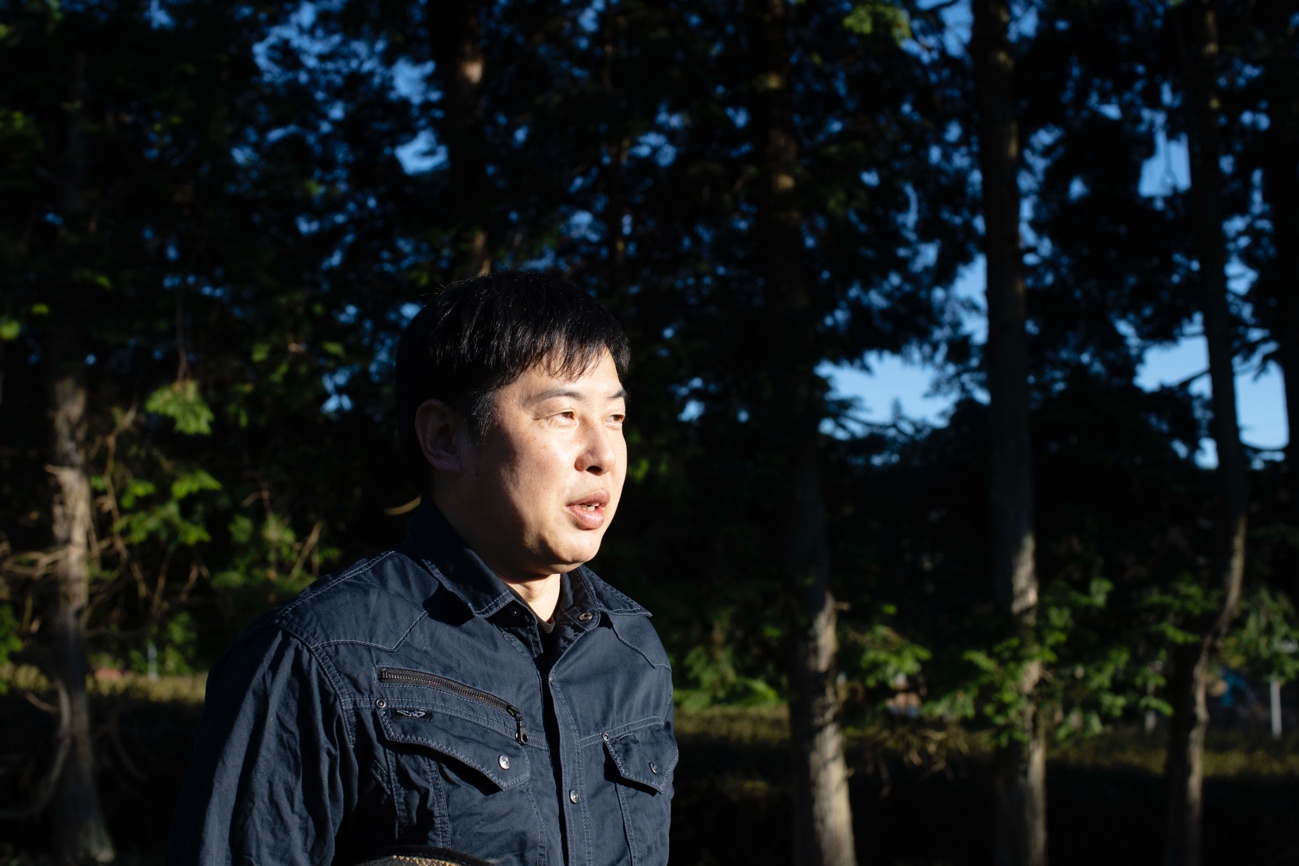

Ishikawa Seicha began cultivating pesticide-free tea early on and was the first Japanese company to produce certified organic Tencha, the raw material for Matcha. We spoke to Tatsuki Ishikawa about their traditional methods of producing high-quality tea and their thoughts for the future.

Tatsuki : In 1967, my father Tetsuo left university at 19 to take over tea cultivation from my grandfather, who had suddenly become ill.

Since he had no experience in tea farming, he started cultivating tea with only the advice of agricultural advisors and senior tea farmers. Still, he was skeptical about the cultivation methods at the time, which used a lot of pesticides, so he started to look for ways to cultivate tea without using these through trial and error.

At that time, there were no reference materials or research results available, so he formed his own hypotheses and steadily verified them over time. They say tea cultivation is suited to warmer climates, but my father set up a tea farm in the Shimoyama area of Toyota City, a higher, cooler area at an altitude of 2130 feet . That high above sea level Shimoyama sometimes reaches 3.2 ºF in winter, and the idea was that pests that damage tea leaves couldn't survive the cold and winter.

Successful cultivation of tea in a highland area doesn't happen overnight. We've suffered cold damage many times, but thanks to my father's (Tetsuo) stubborn character and his firm belief that a time would come when environmentally friendly cultivation methods would become mainstream, we have succeeded in continuing cultivation without ever using agricultural chemicals since we planted in 1978.

The great thing about Tetsuo's father is that he didn't keep his organic farming techniques to himself but also taught the local people. Now, organic farming has become a local initiative that has spread throughout the region.

Tatsuki: I grew up in Toyota City in Aichi Prefecture, a city with a thriving automobile industry, and a lot of the people around me worked for car companies. Growing up, I always had a kind of complex about coming from a family of tea farmers. I didn't want to take over the family business, so I became a professional boxer after graduating from university. Sometimes when I helped out on the farm, though, and that's when I realized the appeal of farming. We do everything for ourselves, from cultivation to processing and sales, and when we get direct customer feedback about the finished tea, or when tea we had a hand in is rated as ‘delicious’ for the first time, it really makes an impression. That was when I decided to quit my job as a professional boxer and become a tea farmer.

Tatsuki: We live in an age when people want tea that’s also beautiful to look at. Toyota wasn’t well known as a tea-producing area, and sales weren’t particularly good. However, after 1990, the problem of pesticide residues began to attract public attention, and the production system was reviewed nationwide. Consumers also began to pay more attention to food safety and security, and this was when the tide started to turn, little by little. Since we were already cultivating without using pesticides, moving toward fully organic farming was a relatively smooth process. In 1997, we became the first private company in Japan to obtain organic certification for our Tencha green tea, the raw material for Matcha. Then in 2001, we became the first company in Japan to get organic certification under the JAS organic standard. Since then, we have obtained IMO organic standard from Switzerland and NOP certification from the United States.

Tatsuki: On the other hand, we felt that there could also be high demand for our products overseas and some wholesalers for those markets asked us to provide larger amounts of organic tea. That was when we began using SNS and so on and actively working on spreading information overseas and starting to work on direct export.

I do those parts jointly with my wife, who studied abroad and worked in an advertising agency. She’s in charge of photography, design, and English translation.

Since we started working with a tea shop in the UK in 2013, we have been exporting more and more tea every year. 2018 was a turning point when we started working with a company in Germany, one of the most advanced countries in terms of organic production in the world, which had been one of my goals. At the same time, we were approached by a national export promotion agency. The Paris branch of the Urasenke tea house served organic Houju no Shiro Matcha at a tea ceremony held at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris as part of Japonisme 2018, the 160th anniversary of the Franco-Japanese friendship, and we demonstrated Matcha milling. During this business meeting, we could directly showcase the appeal of Ishikawa Seicha tea, which really paid off.

Tatsuki: I think single-origin, single-family, single field, and single cultivator are our strengths. We're a small family-owned tea estate, and I feel that we fit the demand for small-scale production.

Overseas customers often ask us detailed questions such as where, how, and by whom the tea is made? or "Do you drink it when you wake up in the morning? At lunchtime? What temperature should the water be, and how should it be brewed? and so on.

I can answer all of these questions as I've studied the tea ceremony, I'm a qualified Japanese tea instructor, I grow my own tea, and I've won many awards.

Left: Mr. Tatsuki with the Grand Prize Cup of the Japan Agricultural Show.

Right: Father Tetsuo with the certificate of the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star.

Tatsuki: In the last few years (before COVID-19), Matcha production has been increasing all over the country. While most are produced quite simply, at Ishikawa Seicha, we use a traditional brick kiln for drying and a stone mill for grinding. In terms of production efficiency, both of these methods are inferior to the more straightforward way, but the color and aroma of Matcha produced in a brick tea oven, which takes time to dry, is much better. Even with today's technology, they say that nothing has been invented to grind Matcha better than a stone mortar. Matcha carefully ground in a stone mortar has a finer grain, and the difference is immediately noticeable in the mouth. Because of our commitment to high quality, we continue to use this method for our Matcha.

In the Japanese-style room, Mr. Tatsuki made us a cup of Kogen no Matcha (powdered green tea) from Ishikawa Seicha.

Tatsuki: As young farmers, we're concerned about the future of agriculture and have formed a group called Yume No Te (Dream Farmers), a group of young, professional farmers working in Toyota City. The average age of farmers, in general, is high, and finding suitable successors is a severe and widespread problem. The group's main goal is to create a society where children can say that their future dream is to become a farmer. We're continually working to raise awareness about the appeal of farming, which is unrivaled by any other industry. One example is a market I organize to share my know-how with new farmers. One of my goals now is to make sure that if my children want to take over a tea farm in the future, I'll be able to hand things over to them and feel proud in terms of the management and working environment.

Tatsuki: For me, Japanese tea is something that I drink, but also something that other people drink.

When I go to the tea plantations, I can see the different expressions of the fields in each season. It helps me feel I’m living in harmony with nature and that the tea is a natural blessing. I’ll be delighted if I can convey this through the taste of our tea.